Welcome to the February edition of Fanning the Flames.

This month’s issue comprises:

1. Announcements:

Poetry launch April 5th, ESU House, Melbourne.

An Illusion of Division? available for purchase

Caleb Caudell’s short story collection to be published in July.

2. Unedifying Editorial: by Andrea Jonathan

3. The Feast of the Goat (2000) by Mario Vargas Llosa review by Lucas Smith

Announcements

Save the date. You are invited to the launch of our first poetry anthology, Wednesday April 5th at ESU House in Melbourne. The anthology was made possible by an ESU major project grant, and they have kindly offered their gorgeous, fully-renovated heritage building for the event. There will be readings, (tasteful in length and quality), refreshments and drinks. Please look out for the event flyer in coming days.

An Illusion of Division? by Father Lawrence Cross is now on sale (here) after a successful launch in Rome. Keep a lookout for a Sydney launch to be held in coming months.

We are extremely pleased to announce that this July we will publish Caleb Caudell’s second book and first collection of stories. The as yet untitled collection shows Caleb mining again the rich vein of Midwestern realism of his 2021 novel The Neighbor (available here), which was shortlisted for the 2022 Indiana Author’s Awards, and also branching out into conceptual and speculative short fiction, I want to say Kafkaesque, but with much higher spirits.

To order titles from our catalogue please visit bonfirebooks.org

Unedifying

Editorial by Andrea Jonathan, Creative Director

There were two publishing related topics in the news media in recent weeks. One was to do with the top ten selling books of 2022, according to Bookscan, being dominated by a certain Colleen Hoover, with notable mentions to Michelle Obama and Prince Harry. The other day I picked up one of Hoover’s books at an airport newsagent and opened to random page. It is living proof that anyone can become a bestselling author, and that the right tawdry fantasies will never fail to sell, however retrograde or unfashionable to the literati.

I haven’t yet had the joy of reading Obama’s memoir, but it was impossible to remain shielded from snippets of Harry’s grandiosely titled confession, Spare, which had been circulating online from the moment the Spanish edition was made available in a botched early release. The press and the public, having whet their appetites with Prince Andrew’s disastrous attempt to face his detractors, could do little but salivate over Harry’s three decades worth of bottled up tabloid sauce, however obviously ghostwritten. If these sordid stories aren’t enough for the discerning reader, the Prince is has created a hardback package bundle for his book which comes with live video-streamed therapy sessions where he will ‘unpack’ his ‘trauma’ for the low price of £30.

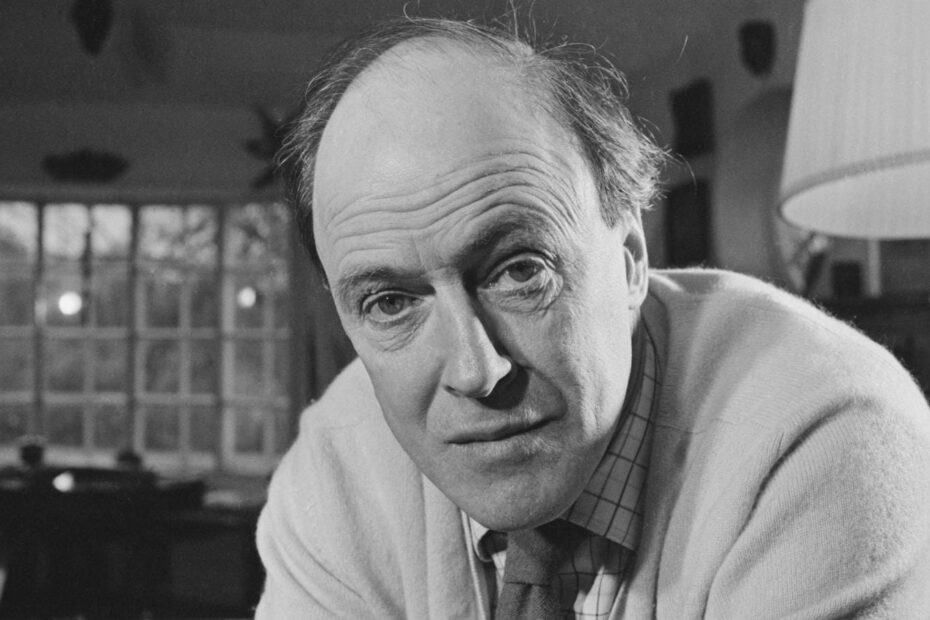

The other recent publishing story of note was the release of revised editions of Roald Dahl’s famous children’s novels which had been rewritten to appease contemporary politically correct sensibilities, going as far as creating new sentences from whole cloth. Despite a half-decade long case of scandal-fatigue I couldn’t resist reading about it, mostly just to find out which lines were deemed the most risqué. One of the rhymes from James and the Giant Peach that was singled out for the memory hole gave me a good chuckle:

The Centipede sings: “Aunt Sponge was terrifically fat / And tremendously flabby at that,” and, “Aunt Spiker was thin as a wire / And dry as a bone, only drier.”

The best they could come up with to replace it was:

“Aunt Sponge was a nasty old brute / And deserved to be squashed by the fruit,” and, “Aunt Spiker was much of the same / And deserves half of the blame.”

I mean come on, are they even trying? Not that I expect much, but even so. I feel almost as sorry for the censors going home that evening after a day’s work as the children who may be accidentally given the revised version by a well-meaning but unaware grandparent.

A spokesperson for the Roald Dahl Story Company went on the record to say: “When publishing new print runs of books written years ago, it’s not unusual to review the language used alongside updating other details including a book’s cover and page layout. Our guiding principle throughout has been to maintain the storylines, characters, and the irreverence and sharp-edged spirit of the original text. Any changes made have been small and carefully considered.”

The managerial use of the French word ‘maintain’ and corporate newspeak of ‘guiding principles’ betrays the true intent of the publisher, which lies beneath the absurdly false equivalence of these textual renovations to updating the cover and layout. In the vein of the Grand High Witch, she attempts to hide in plain sight while plotting the downfall of children. She would have made Dahl proud.

Whilst the mutilation of literature by priggish publishers should always be derided and opposed, it is all too easy to be caught up in reactionary traps, which are often little more than PR exercises designed to inflame passions and drum up publicity for a new product, in this case, a new series of film adaptations of Dahl’s novels.

The Feast of the Goat (2000) by Mario Vargas Llosa

Review by Lucas Smith

Continuing with Bonfire’s Hispanic appreciation, this month I take a look at Mario Vargas Llosa’s The Feast of the Goat (2000).

Broadly realist in scope, this historical novel details the downfall of non-denominational tyrant Rafael Trujillo of the Dominican Republic, in the early 1960s. The plot consists of three main threads: Trujillo himself in his last days of life, the machinations of the assassins and their final fates, and the daughter of one of his cabinet ministers, who returns to Santo Domingo, the capital, thirty years after the assassination to visit her father, one of the few of the old guard lucky enough to be dying of natural causes.

Llosa’s perspective moves freely between reportage, political economy, the inner workings of a tyrannical government and the innermost thoughts of the principal characters. It is in the nature of the free indirect third person that what might in a more innocent age be called “humanising” qualities emerge. Trujillo becomes inevitably a rounded character, with some admirable qualities, not least his dedication and decisiveness and is even at times amusing, for example when griping about his sons’ frittering away the family fortune at the polo in Europe and their lack of interest in succeeding him.

It is in the nature of things also that the well-being of the nation and the well-being of the man in charge merge as one in his mind. While Trujillo may have brought the Dominican Republic through a chaotic period, a war with neighbouring Haiti, and modernised and stabilised the precarious nation, he is blind to the new global consensus of American hegemony emerging around him and he resorts to ever more heavy-handed tactics to keep himself in power.

Also fascinating is the involvement of men of high learning in Trujillo’s cabinet. Indeed several of them forego the pleasures of family life for fine whisky and a dark study, taking to their work with the dedication of a monsignor. The Catholic Church, which previously was a bulwark of the regime comes into Trujillo’s firing line, literally, as American and American-trained clergy begin to protest his abuses, just as American sanctions begin to bite. Trujillo had been trained as an officer by the US Marines when they occupied the Dominican Republic after the first world war, fully imbibing its ethos of service and discipline. He is confused as to why his former allies are laying down sanctions against him.

Although the real-life timeline of the Trujillo assassination is readily available public knowledge, the denouement has the extreme tension of the best thrillers as Llosa depicts the wounded regime’s hunt for the dozen or so conspirators. While Trujillo is killed the half-baked plan to take control of the government fails. The worst excesses occur when regimes of this type feel threatened but remain in power. If you are going to kill the king, not only had you best not miss, you must also seize power immediately. Without the unifying figurehead the sadistic impulses of Trujillo’s chief enforcer are given free reign. A reminder that as bad as things seem in politics, they can always get worse.

Indeed, the aftermath of the assassination is almost as fascinating as the build-up. The figurehead President realises that the vast neighbour to the north will never allow the continuity of Trujillismo. Without further violence he uses a high-profile speech at the UN to manipulate Trujillo’s sons and American public opinion to broker a deal that keeps him in power. The way Llosa shows how appearances and media are forms of power shows he is aware of more modern styles of influence.

Llosa, who won the Nobel Prize in 2010, has been pegged as a conservative, writing against the grain of Latin America’s more radical tradition (or at least the high-profile writers that are translated into English), but it’s hard to find much personal opinion. He is an old-fashioned novelist in the Tolstoyan “whole world” sense, giving full voice to people from every layer of Dominican society and masterfully portraying the universal tragedy of politics.