Welcome to the June 2024 issue of Fanning the Flames. We are excited to share what’s been happening at Bonfire HQ.

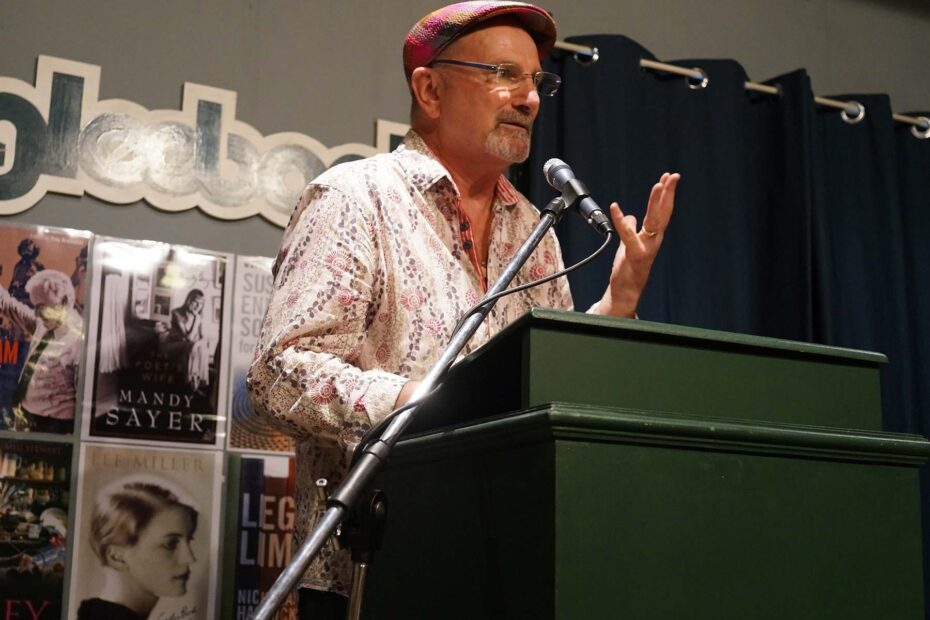

Paul Scully

This month’s issue comprises:

1. Announcements:

The Literate Detective and Other Crimes by Paul Scully

The Librarian of Cappadocia Launch party POSTPONED!

Submissions CLOSED (until January) Pitches OPEN!

Opportunities for writers

2. The Book as a Luxury Item: Editorial by Lucas Smith

3. Le Paysan de Paris (Paris Peasant): Review by Andrea Jonathan

Announcements

We are pleased to announce that Bonfire will publish Paul Scully’s fourth full-length poetry collection The Literate Detective and Other Crimes in March 2025. As the title suggests the first part of The Literate Detective is a sort of diary of a police investigator’s ambivalent unconscious, from his cadet days to first body and first solve:

“Shiv”, Shiva the Destroyer, shiver

-a sonata of spine and fear-

I have loved this word waywardly…

(from “In the Mind of Lithe Evil, 2024”)

The remainder of the book builds on Scully’s signature historical, theological and philosophical themes as well as quiet reflections on life in suburban Sydney. Scully is an AusPo veteran, who, unusually, does not come from a university background but rather from a professional career as an actuary (echoes of Wallace Stevens). His work has been shortlisted in major prizes including the Australian Catholic University Poetry Prize and the Newcastle Poetry Prize. Scully’s work has received praise from, among others, Judith Beveridge, David Musgrave and Caitlin Maling but perhaps in no more gratifying terms than this from Les Wicks in his launch speech for Scully’s first collection in 2014: “I’ve got some bad news for all my fellow poets out there…I have to warn you that the competition has just got hotter.” You can find more information about Paul here. Release date: March 1st, 2025.

The launch for The Librarian of Cappadocia, scheduled for July 21, has been POSTPONED. Bishop Themi, who was going to launch the book, is unable to leave Africa for the time being. Stay tuned for the details of the new date. The silver lining is that it will certainly be warmer in Melbourne when the time comes.

Manuscript submissions are closed until January 2025. However we are open for pitches for the new Bonfire Monograph series. Inspired by our brother in indie publishing, Wiseblood Books, (check out their excellent list here), we are launching an occasional series of stand-alone essays on literary and artistic figures, literary culture and philosophy. We have a couple titles already in the works, the details of which will be announced soon. Too short for a book, too long for an article, finished essays should be between 8,000-15,000 words and have an appreciative tone tempered with discernment. Reappraisals of established or canonical figures (writers, artists or musicians) are welcome as well as assessments of living figures who have yet to attract substantial scholarly attention. Issues to explore could include (but are certainly not limited to): problems facing Australian writers, intersections of religion and culture, the place of politics in art or “stuck culture”. While our focus is Antipodean there is scope for breadth. Pitches should include estimated word count, why you are enthusiastic about your topic and your publishing record (if applicable).

Email pitches to info@bonfirebooks.org with MONOGRAPH in the subject line.

Our friends at the English-Speaking Union (Victoria Branch) have launched three new projects designed to assist writers: A Writer’s Residency (with $5,000 stipend), a University Student Fellowship (valued at $1,000, for currently enrolled students only) and a Formal Verse Contest ($8,000 total prize fund). Click here for details and to submit applications/entries. The deadline for all three projects is August 15.

Upcoming titles: Hardly Working by Caleb Caudell (September), The Art of Ryan Daffurn (November)

To purchase Bonfire titles please visit our website.

The Book as a Luxury Item

by Lucas Smith

When I frequent used book shops, which is less often than I would like, I usually have a wish list in hand or in my head. It’s rare that I find more than a few titles from my list but I also have a principle of buying something new—an author I’ve never heard of or a topic I’ve never thought about. To be clear, I don’t mean picking at random, but finding something that catches my eye in the course of browsing the shelves. In this I suspect I am similar to most hardcore readers but very divergent to the general public.

Books are a unique form of entertainment, relatively cheap and convenient, re-usable and provide more hours of diversion than most films, yet to shell out twenty-five to forty-two dollars for a new book feels like a luxury many cannot afford. If you don’t like a tv show you can simply change the channel or try a different series. If you don’t like a movie or a concert at least you can have a laugh or an argument about it with your friends afterwards. But if you don’t like a book, it still takes up space in your house and you’ve expended mental energy, angst and time in deciding that it’s not for you and often you won’t know a single other person who has read it. It’s also not the done thing to return books for a refund, although perhaps it should be.

What to do with books that we don’t want? Despite our name we are not in the habit of burning books. Gifting a bad book is out of the question and giving it away to an op-shop just feels like inflicting it at one remove on someone else for no reason. So, there it sits on our shelf, the half-read reminder of our folly or the limits of our reading abilities.

Books have always been something of a luxury item, but they seem to be paradoxically so in our day, with high barriers to entry despite relatively low cost. It’s simply frictionless to choose another series or film, rather than wade through a book. Yet, in all of the well-worn hand-wringing about the decline of reading, the most simple hypothesis never seems to be aired. What if books are, just, you know, not as good as they used to be? Are fiction and poetry still primarily truth-seeking modes, the best yet devised by mortal men, or are they signals of status or group identification, whichever group it may be? Uniformity of thought and style, predictability of plot, the narrowing of mainstream opinion, all play a role. The canon is the canon for good reason (nearly always) but every era needs its voices. Is it possible that film and television, pound for pound, simply do a better job of portraying the “rushing complexity of contemporary life”, to quote our submission guidelines?

Indie publishers can play a vital role in outflanking, undercutting and overflying the mainstream. Yet nothing is more off-putting than the self-serving moralising of independent (and increasingly of mainstream) publishers who plead with you to purchase their wares, citing some kind of nebulous ethical imperative. Having read many books does not make someone virtuous or even necessarily more interesting to talk to. Books can help to increase imaginative empathy, enlarge perspective and deepen critical thinking, but the reader must assent to those things already. Arguing for the reading of books in moral utilitarian terms will never be satisfactory. You should buy books because you think you will like them, or you want to take a punt on something new. For those like myself, for whom books are simply breath, no argument is necessary.

Le Paysan de Paris (Paris Peasant) (1926)

by Louis Aragon trans. Simon Watson Taylor

Review by Andrea Jonathan

I came across this book amidst a pile of household rubbish awaiting collection in a street behind Bonfire HQ. Amongst it was some Orwell, Waugh, a handful of Russian novels, and Paris Peasant, a curious title of a type of book I had never encountered. Rather than bemoan how someone could allow this modest collection of literature to be pulped rather than walk the extra hundred metres to the charity shop, where it may be read or even perhaps treasured by new readers, I counted my luck and pocketed the lot.

The book begins with The Passage d’Opera, where Aragon illustrates his imaginative visions of the goings on between the nooks and crannies of the famous Parisian shopping arcade. He writes as an interested observer, himself a part of the place, and writes a combination of personal anecdote, mock philosophy and local history. In describing the famous Parisian trade, Aragon appears to attempt to shock the bourgeoisie in his comedic and lyrical musing.

‘Certainly it is not a preoccupation from which caresses are excluded that has lured this whole shifting population of women into this kingdom: indeed they grant perpetual rights to sensual pleasure over their comings and goings. Charming multiplicity of appearances and provocations. Not one who brushes the air like any other. Each one leaves in her wake a different regret, a different perfume. And even though some of them may bring a very gentle smile to my lips because of the sheer disproportion that reigns between their indifferent or frankly ludicrous physique and their infinite desire to please, they still partake in this atmosphere of lasciviousness which is like the rustling of green leaves. Ancient whores, set pieces, mechanical dummies, I am glad that you are so much part of the scenery here: you are still vivid rays of light compared with these matriarchs one encounters in the public parks’

Aragon develops no plot or character, but rather gives us a series of vignettes and thoughts that spiral from each other. It is a surrealist anti-novel, which contains just enough texture, comedy and madness in its prose to encourage the reader to want to find out just where it will take him in the next moment. In the 1920’s Aragon was a founding member of the avante-garde of the surrealist movement which took the dying energies of Dada and infused them into a new literary forms.

In part VXII, Aragon takes tongue-in-cheek aim at the publisher of a Paris literary journal:

“Monsieur le Directeur

Are you not ashamed to be publishing, month after month, a medley of words lacking the general significance that would make it valid in the abstract eyes of thought? Close your petals, periwinkles. What abyss has ever yawned suddenly at the feet of your contributors? Can the purpose of fiction, and the whole jolly atmosphere it involves, the clever mental acrobatics performed by the fictioneers of the human spirit, possibly be worth this whole routine of writing and printing, the corrected proofs, your heart going pit-a-pat each month at the sight of the layout? The heavens unleash a great storm of derision on this type of activity.”

In the final part of the book, “The Peasant’s Dream”, Aragon invites the reader to consider his philosophical challenge of Hegel and Aristotle and explore metaphysics and idealism in a fast-paced, Socratic style, only to twist his conclusions to absurdities or dead ends, playfully flitting in tone and purpose in what I may surmise is a challenge to the intellectual pride of the reader.

There were moments where Aragon’s ‘calculated intellectual insolence’ grew tiresome, or the strangeness of reproducing telephone book advertisements for dog biscuits encouraged a faster page turn or two, but overall I found Paris Peasant to be an amusing, edifying and imaginative journey to the ‘crazy years’ of Paris, one of the greatest periods of literary and artistic creativity of the twentieth century, that continues to inspire writers to this day. There is much to be said for those who can see the extraordinary, and open our minds and senses with wonder to the world around us. If you’ve ever considered a trip to Paris, I would suggest Louis Aragon as your guide.