This month’s issue comprises:

1. Newly Released Titles:

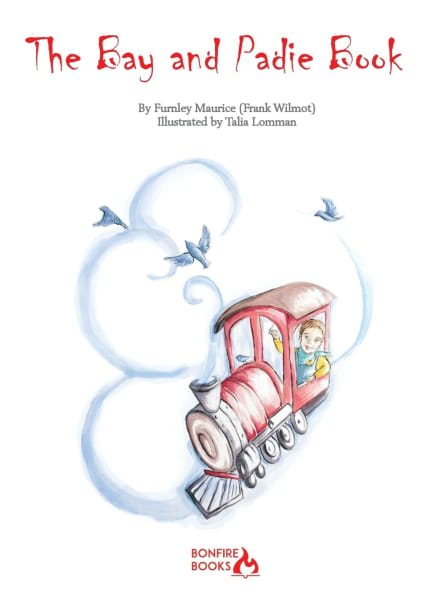

The Bay and Padie Book by Furnley Maurice and Talia Lomman

None But The Crocodiles by Stewart Grahame

2. Upcoming Titles

Holding Patterns by Alasdair F. Cannon

Pinter’s Son Jim by Henry Lawson

An Illusion of Division: An Examination of the ‘Dialogue of Love’ between the Eastern Orthodox & Roman Catholic Churches by Father Lawrence Cross

3. Boeotia and Athens, Editorial by Lucas Smith, Editor-In-Chief

4. Digital Exhibition: Late Summer in Melbourne

5. A Hero of Our Time, Book Review by Andrea Jonathan, Executive Director

Welcome to Bonfire Books’ February newsletter. It has been a big month for us here at Bonfire HQ. Our fifth release None But The Crocodiles is available for purchase here and for international orders here. None But The Crocodiles tells the story of the New Australia experiment of the 1890s, from starry-eyed optimism to grim reality. Thanks to our intern Lily Hull for the jacket painting.

Our sixth release is a collection of children’s poems by Furnley Maurice, The Bay and Padie Book is available for purchase here and for international orders here. Originally written in 1917 for the author’s two young boys, this new selection is the perfect way to introduce children to poetry. Poems range in theme from household mishaps to child-friendly musings on the cosmos, whimsical Australianisms and a mischievous cat and is fully illustrated with original contemporary watercolours by Talia Lomman

We are very happy to announce that a few weeks ago we signed our second living author, Alasdair Cannon. Alasdair is originally from Townsville and lives in Brisbane. In June we will publish his debut collection of essays, Holding Patterns, a unique blend of memoir, cultural criticism, psychoanalysis and Nabokovian wordplay, Holding Patterns takes aim at everything from R U OK? Day to Obama’s foreign policy record, and that’s just the first essay. Alasdair comes with a ringing endorsement from former editor of The Lifted Brow Sam Cooney:

“There’s no writing being published in Australia that is quite like Alasdair Cannon’s – and so we are fortunate that he has dedicated himself to the chosen subjects of these essays, and with the style and brio that is evident throughout. Ranging across the spectra of politics, culture, philosophy, economics, and personal memoir—and the nexus of each of these topics—here we have an ambitious yet still accessible collection of work that should announce a new Australian literary voice.”

We are delighted to add Alasdair to the Bonfire stable. You will be hearing much more about Holding Patterns in the coming months. Please see the Upcoming Titles section below to read a short excerpt.

We are also extremely pleased to announce that we will publish An Illusion of Division: An Examination of the ‘Dialogue of Love’ between the Eastern Orthodox & Roman Catholic Churches by Father Lawrence Cross. A work many years in the making, An Illusion of Division is Father Cross’s deep analysis and reflection on 20th century reconciliation efforts between the Roman Catholic and Orthodox Churches.

Newly Released Titles

The Bay and Padie Book by Furnley Maurice, illustrated by Talia Lomman

The Bay and Padie Book is one of the finest examples of Classic Australian Children’s poetry. Originally written in 1917 for the author’s two young boys, this new selection is the perfect way to introduce children to poetry. Poems range in theme from household mishaps to child-friendly musings on the cosmos, whimsical Australianisms and a mischievous cat. Fully illustrated with original contemporary watercolours by Talia Lomman, The Bay and Padie Book is a bedtime essential. Ages 4-9.

None But The Crocodiles by Stewart Grahame

In the late 1890s a group of disillusioned Australian men and women under the guidance of a spellbinding unionist named William Lane, settled in Paraguay to build a perfect society. The “New Australia” experiment soon faltered, foundered and fractured on the shoals of daily practicalities and human nature. Stewart Grahame, who spent “over five hundred nights in a mud hut” at New Australia pieces together the fascinating saga of naivete, hope and surprising resilience, using primary documents, interviews, and his own lived experience. First published in 1912, None But The Crocodiles is essential reading for Utopians and idealists of every stripe.

Upcoming Titles

Pinter’s Son Jim by Henry Lawson

Holding Patterns by Alasdair F. Cannon

For now, here is a short excerpt:

My boss, a person in her early 60s, was the director of our organisation. I met her on my first day at the company. I found her charming if a little saccharine. She said we would work closely together, so I would need to understand the ‘crazy world’ inside her mind. A person with a literary sensibility, this early meeting established all the major themes of our relationship—deception, insanity, and authority—and augured her behaviour in the months to come.

The sweetness that belied her vicious underside quickly dissolved after our first encounter. Her false persona began to lapse. I saw tactless moments of dismissal and unkindness: sadistic slips and quick, violent flickers in her eyes. Flashes of otherness would emerge between her words, only to recede immediately, like a light that rises from the depths of a lake and is then drawn backwards, vanishing, while its traces shimmer upon the water’s veneer. Fleeting impressions of disturbing significance, only just hidden, would appear and then they were gone, retreating back beyond the limits of articulation. Her affability was the obverse of a refined, hidden sadism, and like everything we try to hide, these seemingly minor elements of her personality eventually proved decisive. Soon they dominated our interactions and filled the space between us.

Every week she would request new work of me in a vague and ambiguous email or during a rambling and baffling meeting. This work was sometimes completely outside my area of expertise, demanding skills of me that were not in the job description and which I did not have. Usually though it was just far below my skill level, and this was because she couldn’t yet trust me: I was new, you see, and I needed the training they promised to provide later. Determined to prove that I was not worthy of trust or more challenging work, my boss never offered this training to me, and said that everything I completed was wrong. ‘Not good enough,’ she would say. ‘Do it again.’ So I would say, ‘Okay,’ and I would do it again. But by the time I had revised the work, her goals, never entirely clear to me, had changed. Different things were needed. She would discard or ignore the previous work and send me off with new instructions even more baffling than the last. And then the cycle would repeat, the tension rising every round.

My boss had a litany of excuses for this behaviour. She couldn’t pay attention to my work because her medical treatments made her feel unwell. She spoke over me and disregarded my opinions because, being a woman, people never listened to her. ‘Oh,’ I would say. ‘I’m so sorry. I hope you’re okay.’ At the same time, she was creative when condemning me. Where I failed to understand her, I revealed my inability to take instructions. If she didn’t comprehend something, I had poor communication skills. ‘Oh,’ I would say. ‘I’m so sorry. I’ll do better next time.’

Quickly, things worsened. I learned that if I deviated from her instructions in any way, I would be criticised; I also learned that if I didn’t try to add extra, useful things to my work that she hadn’t requested, I would be condemned.

Terrified of being fired, my anxiety raged with a new ferocity. I went to see the organisation’s in-house psychologist. R U OK? Day posters hung on the walls of their office as I completed a mental health questionnaire. I scored 39/40 on this suffering quiz. This meant my symptoms were ‘severe.’ This meant I was not ok. So we spoke about possible causes, and together we reified my pain, made it existential. ‘My life does feel pretty meaningless,’ I claimed. Deferring to the masculine panacea, I said I might start lifting weights to combat the void.

Though it is obvious now, it took me months to realise that her behaviour was the source of my suffering. And in this time where I blamed nothing for my pain, my life became unbearable. I started vomiting before work. Taking diazepam to sleep. Stress fractures appeared in my teeth. Soon I was near-delirious with fatigue, and it was then that I noticed some dramatic ironies in my life. In my savage anxiety, I became excruciatingly aware of the fact that my job was funded by a charitable organisation whose endowment came from a private mental health care company; my father even held shares in that company. Funny, ha ha. And though it was months after the occasion, I noticed that R U OK? Day posters were still everywhere. In the coffee room, the bathrooms, the lifts: the crassly happy yellow-and-black signs were all around, xanthic, lambent, ambient, beaming from the walls. The colour of madness, the colour of nothing. With their strange mix of care and authority, they relentlessly questioned my mental health. In response, I could only quote Pulp Fiction’s Marsellus Wallace. Nah, man, I thought. I’m pretty f—– far from okay.

An Illusion of Division: An Examination of the ‘Dialogue of Love’ between the Eastern Orthodox & Roman Catholic Churches by Father Lawrence Cross

The Dialogue of Love was a series of correspondences and events undertaken between leaders of the Roman Catholic and the Eastern Orthodox Churches from the mid-1960s to the mid-1990s, beginning with the famous embrace between Pope Paul VI and Ecumenical Patriarch Athenagoras at the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem in 1964. Marking the most significant modern attempt at rapprochement between the churches, the Dialogue led to deeper mutual understandings, fruitful relationships and a recognition of spiritual blessings.

With his unique perspective as a Roman Catholic priest in the Eastern tradition, and his belief in a deep and abiding ‘mystically real bond’ between the Churches, Father Lawrence Cross brings a wealth of research to his examination of the Dialogue of Love, asking throughout the important question, to what degree is the division between East and West merely an illusion?

Moving from practical considerations to the workings of the Spirit, to dialogue as theology, with extensive notes referring to Latin, Greek and Russian primary source material, An Illusion of Division Is a comprehensive study of a profound revelatory unfolding in Church and world history that will be of interest to Christians of all traditions who thirst for unity.

Father Lawrence Cross was born in Sydney in 1943 and received the Catholic faith from the very Irish Australian Church of his childhood, but as a young man he fell in love with the Russian Byzantine tradition. It is there ever afterwards that he has expressed this same faith. Consequently, all his ecumenical and theological activity has been dedicated to the reconciliation of Orthodox and Catholic Christians. He received most of his high school education on a choral scholarship from St. Mary’s Cathedral, Sydney. He graduated in Arts from the University of Sydney and later read History in St. John’s College, Oxford. He is a Doctor of Theology in the Melbourne College of Divinity. From 1963 to 1980 he was a member of the one-time Society of St. Gerard. There his keen interest and love of Orthodoxy was deepened and extended. From 1981 to 2013 he taught theology in the Australian Catholic University and is presently an Honourary Fellow of the University. No one has been more active locally and internationally in the cause of Catholic/Orthodox reconciliation, generating ecclesial events and projects to expand the Churches’ knowledge of each other and of their particular experiences of Tradition. He is in demand as a speaker at international theological conferences, with a record that spans from Oxford to Serbia and from Moscow to Rome. His research continues to appear in theological journals worldwide, including The Ecumenical Review, One in Christ, St. Vladimir’s Theological Quarterly, Irish Theological Quarterly, New Blackfriars, Studia Patristica, and the Newman Studies Journal, to name a few. He is the founder of the international conference series Orientale Lumen: Australasia and Oceania, and with Professor Pauline Allen, of Prayer and Spirituality in the Early Church (now continuing as (Early Christian Centuries). He is the pastor of the Russian Byzantine Catholics in Australia, based in the Russian Catholic Community at Holy Trinity-St. Nicholas, Melbourne. He was supported in all his work by his beloved Diane (d. 2011) and has two sons, Nicholas and Patrick.

Boeotia and Athens

Editorial by Lucas Smith

It is frequently observed that Australia is an urbanised nation with a rural mythos. ‘Bush tales written by urbanites’ is a reasonable precis of Australian literature. While most of the population live and have always lived in the cities, the archetypal Australian story is a person—usually a woman, perhaps with an infant or a dog—alone in the expanse of the Bush facing some human or inhuman terror.

One half of Bonfire recently left Gotham for a seaside town, so the rural/urban distinction has been on our minds recently. The late Les Murray, whose posthumous volume, Continuous Creation, will be released tomorrow by our esteemed competitor Black, Inc., left some reflections on these matters in a 1978 essay called “On Sitting Back and Thinking About Porter’s Boeotia”. Peter Porter’s, that is.

Boeotia (pron. Bee-oh-sha) was the district to the north-west of Athens, centred on Thebes. It was the rustic part of Hellas. Woop-woop or Back-of-Bourke, in our language, a place sophisticated Athenians looked down on. For our purposes the significance is that Boeotia produced poets, most notably Hesiod and Pindar, while Athens produced the celebrated dramatists of Classical Greece. Boeotia versus Athens, poetry versus drama, provincial versus metropolitan, traditional versus progressive.

Boeotian is expansive, radiant, earnest, natural; it is roughly equivalent to Murray’s usage of “sprawl” in his famous poem “The Quality of Sprawl”. Athenian is ironic, dramatic, self-aware, satirical. They are both categories of the imagination rather than literal qualities. One can live in the city and be Boeotian and vice versa.

Les, if you’ll allow the familiarity, is a Boeotian. That “Sitting Back” in the title of his essay is a Boeotian gesture if there ever was one. Peter Porter, whose poem “On First Looking Into Chapman’s Hesiod” serves as the catalyst to his musings, is an Athenian.

Ensconsced in his Paddington flat, Porter, is shocked to recognise in the work of Hesiod, “Australia, my own country

And its edgy managers—in the picture of

Euboeaen husbandry, terse family feuds

And the minds of gods tangential to the earth.”

“Yes,” he continues, “Australians are Boeotians / thick as headlands.”

Les begins his article by observing that “Athens has recently oppressed Boeotia on a world scale, and has caused the creation all over the world of more or less Westernized native elites which often enthusiastically continue the oppression.”

Much has been made in recent decades about the Australian cultural exodus, a necessary corollary to the cultural cringe and part of the oppression of Boeotia by Athens, but it is not so much that our most talented leave the lucky country but that the headline cultural names of the last fifty years (James, Greer, Porter, Murray, Murnane, Carey, Boyds Martin and Arthur), all left (fled) Australian cities.

We are living now in a much different literary moment in which, even before lockdowns, place seemed to have diminished in importance. Increasingly, if you are from one large Western metropolis, you are from any of them. The decline of literary culture in the face of the screen (a long topic for another essay) is one factor. The most important place in our time might be the couch. So-called “online communities” spring up by preference and necessity to provide a poor facsimile of the frisson of the city in the comfort of one’s own bedroom.

New York and London are still probably beacons for aspiring Anglophone writers (LA is probably the better analogue of Athens), just as Melbourne is to country Australians, but they are all shadows of their former selves, increasingly expensive, increasingly fractured. The future of artistic endeavour is, may Allah forgive me for uttering this word, fractal. It may still be advantageous to live in certain neighbourhoods in certain metropoles but it is no longer necessary, and might even be stifling.

As for Australia, Les writes, “It would be something indeed, to break with Western culture by not taking, even now, the characteristic second step into alienation, into elitism and the relegation of all places except one or two urban centres to the sterile status of provincial no-man’s-land largely deprived of any art or any creative self-confidence.”

Porter ends his poem with an emphatic defense of the freedom Athens offers:

“…but I still seek

The permanently upright city where

Speech is nature and plants conceive in pots,

Where one escapes from what one is and who

One was, where home is just a postmark

And country wisdom clings to calendars,

The opposite of a sunburned truth-teller’s

World, haunted by precepts and the Pleiades.”

But Murray says, “I cannot believe in that ‘permanently upright city’ of willed disengagement from the past and unending personal development.”

At Bonfire, we aspire to say, “Porque no los dos?”

I will conclude this feuilleton with some final words from Les in defense of Bonfire’s Australian focus: “A nation, a people, is always of more value to the rest of mankind if it remains itself..It may be reserved for us [Australians] to bring off the long-needed reconciliation of Athens and Boeotia.”

Digital Exhibition

This month continues last month’s theme of Heidelberg school Victorian landscapes and characters from the bush and goldfields. Some of these places have changed little to the present day. The Heidelberg Artist’s Trail signposts these locations, many of which are littered around the present day outer suburbs of Melbourne.

The Gold Puddlers by Walter Withers (1893)

An Old Bee Farm by Clara Southern (1900)

The Village by Jo Sweatman (1931)

A Hero of Our Time by M. Yu. Lermontov (1840)

Review by Andrea Jonathan

Written as an unconnected series of stories and journal entries of the Russian military officer Grigory Alexandrovich Pechorin and set in the mountains of the Caucasus, A Hero of Our Time is a critique of Russian high society as much as it is of its flawed Byronic hero. One of the mistakes I used to make as a young reader attempting older texts was to get bogged down and often put-off by lengthy and detailed historical introductions by learned but well-meaning publishers. I now simply begin reading, and trust the author to explain his world to me, returning to the introduction later if I get around to it.

Pechorin resembles in several respects what any man at the time might aspire to be; charming, handsome, a fearsome soldier, a good shot and adored by beautiful women wherever he may find them. Having left the salons of St. Petersburg for the rugged mountains of the Caucuses, described in elaborate visual detail, Perchorin finds himself embroiled in scandals with women and fights to the death with their male pursuers, driven by a combination of sly, cunning and simple boredom with the world.

After breaking the heart of yet another damsel, in this case a visiting princess, Pechorin romanticises his rejection of romance and fidelity to bachelorhood:

And now, here in this wearisome fortress, I often ask myself, as my thoughts wander back to the past: why did I not wish to tread that way, thrown open by destiny, where soft joys and ease of soul were awaiting me?… No, I could never have become habituated to such a fate! I am like a sailor born and bred on the deck of a pirate brig: his soul has grown accustomed to storms and battles; but, once let him be cast upon the shore, and he chafes, he pines away, however invitingly the shady groves allure, however brightly shines the peaceful sun. The livelong day he paces the sandy shore, hearkens to the monotonous murmur of the onrushing waves, and gazes into the misty distance: lo! yonder, upon the pale line dividing the blue deep from the grey clouds, is there not glancing the longed-for sail, at first like the wing of a seagull, but little by little severing itself from the foam of the billows and, with even course, drawing nigh to the desert harbour?

So precious is his liberty that he cannot abide the reciprocal obligations arising from friendship. After describing a new acquaintance, he confesses:

Werner and I soon understood each other and became friends, because I, for my part, am ill-adapted for friendship. Of two friends, one is always the slave of the other, although frequently neither acknowledges the fact to himself. Now, the slave I could not be; and to be the master would be a wearisome trouble, because, at the same time, deception would be required. Besides, I have servants and money!

It is remarkable just how ‘modern’ Pechorin’s defects appear to be. With some paring back of his valour in combat and literary and philosophical musings, our hero could have applied to him several contemporary diagnoses of the modern male – ‘commitment-phobic’, ‘Peter-pan’, ‘failure-to-launch’ or ‘pick-up artist’ are a few that come to mind. It would appear that present-day ills have origins deep into the past, or is the problem that we hold up an ideal of social relations that has never truly existed?

I returned home by the deserted byways of the village. The moon, full and red like the glow of a conflagration, was beginning to make its appearance from behind the jagged horizon of the house-tops; the stars were shining tranquilly in the deep, blue vault of the sky; and I was struck by the absurdity of the idea when I recalled to mind that once upon a time there were some exceedingly wise people who thought that the stars of heaven participated in our insignificant squabbles for a slice of ground, or some other imaginary rights. And what then? These lamps, lighted, so they fancied, only to illuminate their battles and triumphs, are burning with all their former brilliance, whilst the wiseacres themselves, together with their hopes and passions, have long been extinguished, like a little fire kindled at the edge of a forest by a careless wayfarer! But, on the other hand, what strength of will was lent them by the conviction that the entire heavens, with their innumerable habitants, were looking at them with a sympathy, unalterable, though mute!… And we, their miserable descendants, roaming over the earth, without faith, without pride, without enjoyment, and without terror—except that involuntary awe which makes the heart shrink at the thought of the inevitable end—we are no longer capable of great sacrifices, either for the good of mankind or even for our own happiness, because we know the impossibility of such happiness; and, just as our ancestors used to fling themselves from one delusion to another, we pass indifferently from doubt to doubt, without possessing, as they did, either hope or even that vague though, at the same time, keen enjoyment which the soul encounters at every struggle with mankind or with destiny.

Here Lermontov elucidates the self-doubt and emptiness of the over-educated and faithless Pechorin – a prisoner of the freedom obtained from unshackling himself from the ‘delusion’ of his professedly ‘exceedingly wise’ ancestors. It is this un-anchoring from place and truth that has set Pechorin on his path of foolishly perilous misadventure, seeking thrills rather than the dull stability of home and hearth:

The young men, Grushnitski amongst them, were having supper at the large table. As I came in, they all fell silent: evidently they had been talking about me. Since the last ball many of them have been sulky with me, especially the captain of dragoons; and now, it seems, a hostile gang is actually being formed against me, under the command of Grushnitski. He wears such a proud and courageous air…

I am very glad; I love enemies, though not in the Christian sense. They amuse me, stir my blood. To be always on one’s guard, to catch every glance, the meaning of every word, to guess intentions, to crush conspiracies, to pretend to be deceived and suddenly with one blow to overthrow the whole immense and laboriously constructed edifice of cunning and design—that is what I call life.

The “malicious irony” of the title A Hero of Our Time for such a protagonist poses the question of what is behind the popular enthusiasm for such a figure? That Pechorin represents the physical and intellectual vanity and materialism of the youth of his time, and yet retains, in the admission of the publisher of his journals, a certain likeability and heroism, indicates the flaws of the reader as much as Perchorin himself – each of us a swooning damsel or furiously betrayed suitor.

Lermontov makes references to his contemporaries Goethe and Pushkin, of whom we could expect his readers to be familiar, and includes some dialogue in French for moments of affectation or melodrama, widely spoken by Russia’s nobility at the time. Considered one of the first great Russian novels, A Hero of Our Time, while slightly slow to start, was highly entertaining and had me darkly cackling towards the end.