This month’s issue comprises:

1. Announcements:

Holding Patterns by Alasdair Cannon is launched!

New signing: Albany Unravelled by Dr. Steffan Silcox and Douglas Sellick

Australian Poetry Anthology: Call for Submissions

2. Banning Books: Or How I Learned To Stop Worrying And Love Censorship: Editorial by Andrea Jonathan, Executive Director

3. Concrete Abstraction: Groupo Ruptura and Noigandres : A Digital Exhibition by Lily Hull

4. Last Letter to a Reader by Gerald Murnane (2021): Review by Lucas Smith, Editor-in-Chief

Holding Patterns by Alasdair Cannon

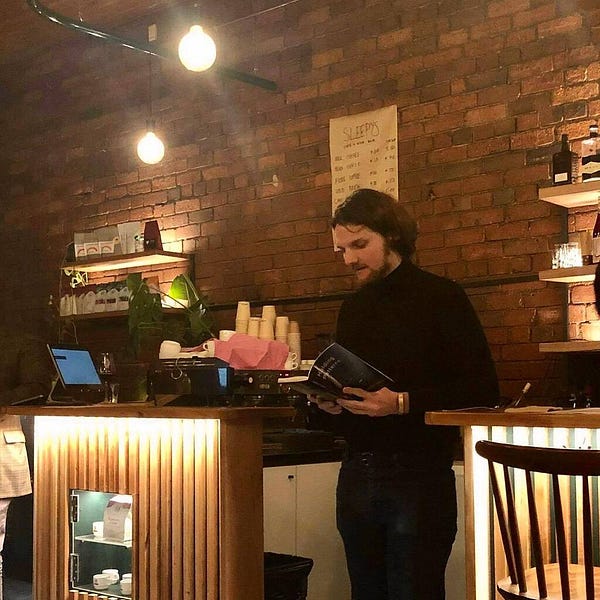

Holding Patterns is launched! Thank you to everyone who came out to one (or more) of Alasdair’s three launches and all those who have supported the book so far. A couple photos are below. Read the Townsville launch speech by Kristell Scott on our website here.

Holding Patterns is available here (Australian orders) and here (overseas orders). Also in stock at Brunswick Bound and Neighbourhood Books, both in Melbourne. More retailers to come.

2. New signing: Albany Unravelled by Dr Steffan Silcox and Douglas Sellick

We are pleased to announce that we will publish a new history of Albany, Western Australia by Dr Steffan Silcox and Douglas Sellick. This monumental work that expands and corrects the historical record was compiled and written to commemorate the upcoming Bicentennial of one of the nation’s most historically significant regional towns in 2026. Albany Unravelled will be published in mid-2023. In their foreword to the book, Professors Stephen Foster and Peter Spearritt write, “Douglas Sellick and Steffan Silcox have put in a prodigious amount of effort in assembling these documents, along with explanatory commentary. Both authors live in Albany and manage to convey their fascination with its rich history. They have gone to great pains to check some of the key claims about Albany’s history, often taken for granted by generations of historians, not always going back to the original sources. So, this book will stand as a well-researched collection for many years to come.”

More details to come.

3. Submissions for our 2023 poetry anthology are open.

Thanks to a grant from the English-Speaking Union (Victoria Branch) Bonfire Books will showcase the finest in contemporary verse in early 2023.

Submission Guidelines

Please send up to 3 poems in a .pdf, .doc or .docx attachment to info@bonfirebooks.org. with “Your Surname-POETRY” in the subject line. Poems should be no more than 100 lines each and no more than five pages per full submission. Poems may be previously published in periodicals within the last five years but not in books. Poets will be remunerated and will receive a copy of the anthology. While all poetic forms and themes are welcome, preference will be given to music, sense, meaning and felicity of language. Submissions close November 1 and are open to Australian citizens and Australian residents.

That’s all from us for now but keep your inboxes peeled for a very special announcement later this week.

-Lucas

Banning Books: Or How I Learned To Stop Worrying And Love Censorship

Editorial by Andrea Jonathan

It would appear that over the past few months, Bonfire’s raison d’être has come sharply into the spotlight. The latest word being bandied about in the world of book sales and publishing is ‘banned’, which is only a step or two removed from ‘burned’, giving a pyromaniacal sense of theatricality to a topic area more commonly associated with blue-rinse librarians in mustard cardigans. ‘Banned books’ are more popular than ever, and any up-and-coming author worth his salt would dream with elation about claiming a title in such an august pile.

Penguin, Barnes and Noble, Books-A-Million and many others of the largest publishing and bookselling chains are hosting ‘Banned Book Weeks’ and have special stands and landing pages dedicated to rousing a sense of the illicit about this newly minted sales category. Some of these dangerous titles include To Kill A Mockingbird, A Handmaid’s Tale, Huckleberry Finn and Harry Potter. Luckily, I have a cache of samizdat bootlegs of such titles stored safely away from the prying hands of the censors, or the next generation might be deprived of the character-forming benefits of trudging through the very literary turgidity, shallow characters and hackneyed plotlines that made me the man I am today.

Many of the more recent book-bannings have come from the conservative end of the political spectrum in the United States, which has until quite recently maintained a position of moral superiority or victimhood that censorship is wrong or unfair, or alternatively one of wishful thinking, that the ‘marketplace of ideas’ will decide which books will and won’t be read. Now conservative school boards are ‘banning’ books that they deem to be harmful, whilst lamenting the bans on books, such as Harper Lee’s mentioned above, that they believe reflect their own civil rights-era values. The pot calls the kettle ‘African-American’.

In a paradigm of ‘living one’s truth’ it becomes difficult to make appeals to the common good, which cannot be agreed upon due to the radical subjectivity of the episteme. What is left is an ironic form of bi-partisan back scratching – I’ll cancel yours, if you’ll cancel mine. That way we can both claim to be underdogs while we one-click add-to-cart ‘banned’ book lists and clutch the pearls upon our quivering breasts as we are reminded in a ‘Banned Books Week’ Zoom conference of the stern warnings of Orwell.

Now it may be all well and good for this parody of censorship to be exploited as a marketing technique, but what about the impacts of gatekeeping on young minds, and the personal libraries which continue to be built from real paper books, usually bought in bricks-and-mortar stores? It can’t be denied that there is a risk that the breadth of ideas and so called ‘voices’ is throttled by an ideological consensus and a philosophical approach to literature that is radically subjective and therefore bereft of the humility that enables one to be fair and open-minded and therefore learn from the greats. But that is a broader discussion – what I beg for is some real, hard censorship that could help turn the artifice of what are ‘banned books’ or sometimes referred to in double speak (forgive me) as ‘challenged books’, into the reality of genuine litmus-tests of dangerous ideas. A censor can be a catalyst to help one explicate one’s ideas at a higher or more allegorical level. With every home-printer or personal computer a potential paper or digital printing-press, we should not fear censorship. What we should really fear is that young people stop reading altogether. For some, a sense of subterranean peril lurking between the lines of a page might be exactly what is needed to solve this problem.

To order titles from our catalogue please visit bonfirebooks.org

Concrete Abstraction: Groupo Ruptura and Noigandres by Lily Hull

“Poems are to be seen and paintings are to be read!”

Richard Peltz – Aesthetic Theory and Concrete Poetry: A Test Case

At university I had the pleasure of dabbling in courses related to both creative writing and the visual arts. It wasn’t often that I saw the two collide and yet in my final year I learnt about a group of artists and writers that challenged this. The concrete art movement of the 1950’s shows an interesting transition from the preceding avante-garde of dadaism and futurism. From São Paulo came a separate establishment of artists who sought to define their individuality through language, the visual form and their dual comprehension.

The title “concrete” suggests the rejection of the art of subjectivity. Concrete art is surface level. It does not extend beyond what it is. Simplicity, geometric abstraction and objectification replaced narrative, becoming the key values amongst the visual artists of the Groupo ruptura and the poets of the Noigandres.

The 1956 opening of the “I Exposição Nacional de Arte Concreta” in the Museu de Arte Moderna of São Paulo was the first in Brazil to showcase paintings, sculptures, and poster poems side by side. This digital exhibition reflects the pivotal amalgamation of art, poetry and design that came to define the concrete movement, showcasing the various pieces that were presented in Sao Paulo in 1956 and the years that would follow.

Concreção (Concretion), Luiz Sacilotto, 1952.

terremoto, Augusto de Campos, 1956

Composição em triângulos (Composition in Triangles), Alexandre Wollner, 1953

Beba Coca Cola (Drink Coca Cola), Décio Pignatari, 1957

Untitled, Waldemar Cordeiro, 1952

Last Letter to a Reader by Gerald Murnane (Giramondo, 2021)

Review by Lucas Smith

Australia’s oddest literary export, Gerald Murnane, is in the overseas media again, this time with a profile in The New Yorker (Aug 1, 2022). The occasion is the UK publication of his fourteenth and “final” book, Last Letter to a Reader, which consists of fourteen rather meandering “reports”, one for each of Murnane’s published books, including the Last Letter itself. As the New Yorker writer notes this is the fourth time Murnane has declared a book his last.

83 year-old Murnane is everything a stereotypical literary superstar is not. He is not well-travelled, having never flown in an airplane and rarely leaving the State of Victoria; he is not a spokesperson for any sort of cause; he lives in Goroke, a small agricultural service town roughly equidistant from Melbourne and Adelaide; he writes grammatically correct English. Okay, I’m joking about that last one. But he does have a fastidious commitment to grammar, like he’s building a ship in a bottle.

I am a relative novice when it comes to Murnane, having only read The Plains, Border Districts and the present text. There is a lot to like in Murnane’s commitment to his sensibility, his integrity, his clearly sincere independence from praise and criticism alike, and his insistence on good usage. In an age that pressures us to join in, Murnane’s insistence on an idiosyncratic and indeed sometimes wholly private vision is striking. All the random associations, atypical interests, recursive obsessions and non-linear trains of thought that anyone who pays attention to their own mind will notice bubbling away in themselves, but that most people keep private most of the time, Murnane lets out in his recursive, dream-like, associative, almost plotless and placeless novels.

The trouble is that Murnane never seems to move out of his own “memory-palace”, which is why, for me his books tend towards tedium, no matter how exquisitely built. If subjectivity is all there is, then why wouldn’t I spend my time with my own subjectivity rather than someone else’s? That is to say, if subjectivity is all there is, then learning about the world is in an important sense impossible, so why not just refine my own interiority, because that’s all that is possible anyway. It seems obvious to me that if I believed this, which I emphatically don’t, I wouldn’t see the point of engaging with literature at all. Looking into another’s mind is how we escape subjectivity, to be sure, but instead of saying, “This is how I see the world,” Murnane says “this is how someone could see something that they might define as a possible world.” The ship looks indomitable, but it’s not going anywhere in that bottle.

In Murnane’s spirit though, allow me to give one of my own images. In a local government video promoting tourism in his region Murnane appears for a few seconds, not speaking, not in situ at the typewriter, not in front of a row of books, but working a bandsaw in the Men’s Shed. He is un-named and un-credited. You only know it’s him if you already know what he looks like. The world-famous writer working with his hands with country folk hundreds of miles away from the nearest metropole. This led me on a reverie imagining I was in charge of the West Wimmera Council Tourism campaign. Think of the slogans. “Walk the original Plains of Murnane!”

Murnane seems aware of his reputation, as he throws out some juicy academic bait in the second to last report. Recounting the years before his writing career took off, he writes, “but I had drawn much strength for many years from an achievement unknown to my colleagues or even to my few friends: I had published, under a pseudonym, but by a reputable publisher, a moderately well-received volume of poetry.” This book, if it exists, is still undiscovered—first one to figure that one out gets an Early Career Researcher Fellowship.

An old-fashioned snob would say Murnane is under-appreciated, his talent wasted on Goroke. Can anything good come from Nazareth? A different kind of snob would say that his work in the Men’s Shed is more real, more useful than his books. Here at Bonfire we like to allow people to be multi-dimensional. In a moment of humble poignancy fitting a (supposed) final statement, Last Letter ends with original lyrics in Hungarian and an original melody to match, the score printed on the page. Words have been exhausted, only music will do.